Plugging the RTI Act loopholes

On the face of it, the Right to Information (RTI) Act has empowered the citizen to a large extent. However, it seems obvious that the RTI has not been understood properly, given that the impulse to take shelter under the Official Secrets Act (by the Executive), the Parliament Privileges (by the Legislature), the Contempt of Court Act (by the Judiciary), still prevails to a considerable extent.

On the face of it, the Right to Information (RTI) Act has empowered the citizen to a large extent. However, it seems obvious that the RTI has not been understood properly, given that the impulse to take shelter under the Official Secrets Act (by the Executive), the Parliament Privileges (by the Legislature), the Contempt of Court Act (by the Judiciary), still prevails to a considerable extent.

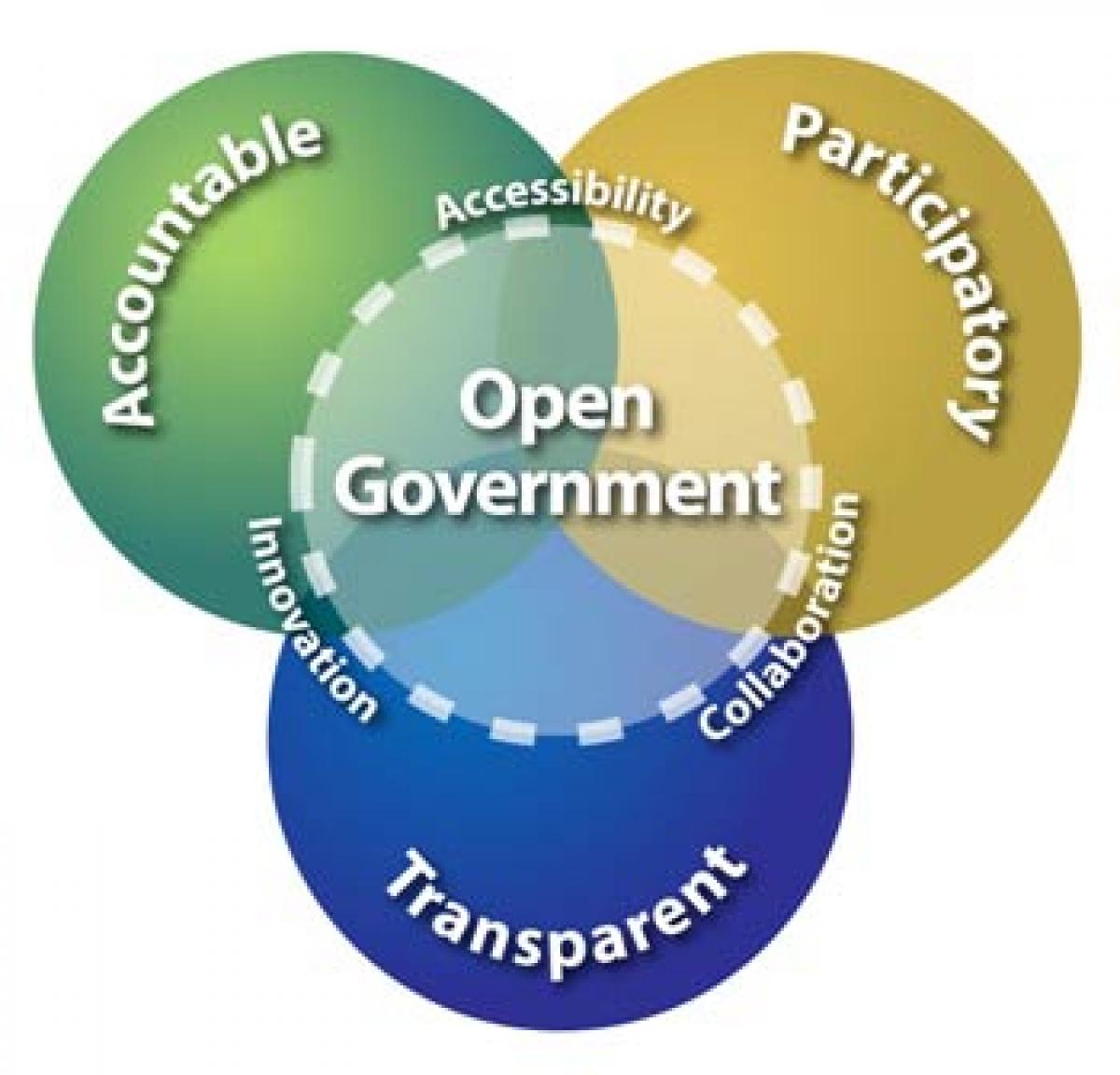

The RTI Act is not just a law promoting disclosure of information but a strategy to improve delivery of public services through citizen-enforced accountability. Disclosure of information is the rule and exemption an exception under it. Section 4 of the Act mandates pro-active disclosure of basic information about the department, such as the names of the Minister concerned, key staff, contact details, organisational structure, the services provided and programmes run, the departmental budget and ongoing updates on expenditure and public procurement, among other things.

However, the structure and dynamics of public administration have changed from welfare to regulatory to commercial activities. The government holds a lot of sensitive information, the disclosure of which may not, at all times, be in the interest of the nation or the State or serve any public interest.

While the call for open government data endorses the proactive disclosure requirement under the RTI Act, there is a need to develop a robust information disclosure policy to mitigate the unintended consequences of open data while fostering transparency in public administration. The Official Secrets Act, 1923 typically provides legal embargo against espionage and unauthorised disclosure of information relating to security and intelligence (which anyway qualify for exemption from disclosure under the RTI Act) and is subject to damage assessment.

Based on the sensitivity of the information held by the Public Authority, it is classified and treated as per Sec 156 & 157 of State Secretariat Office Manual as top secret, secret and confidential (care being taken to ensure that the Top Secret category is not unnecessarily employed). Whereas under the RTI Act, exemptions set out under Sections 8, 9 and 24 form the only basis for refusing access to government information requested under the Act.

The said exemptions are either mandatory or discretionary and can be disclosed if public interest in disclosure outweighs the harm to protected interests of the RTI Act. However, an administrative authority in which discretion is vested is supposed to exercise it by taking relevant considerations into account and by excluding irrelevant considerations. And it is a settled position of law that the decision of an administrative body is subject to judicial review if it has not exercised its discretion legally.

So what needs to be considered under the public interest test?

Factors favouring disclosure of information are government accountability, public participation, public awareness and promoting human rights. Factors favouring non-disclosure are invasion of privacy, statutory prohibition and other exemptions under Sections 8, 9 and 24 of the Act

And factors that are irrelevant for consideration under the Public Interest Test are: a) that the information may be misused, misinterpreted or misunderstood by the applicant; and b) that the disclosure might cause embarrassment to the government.

In view of the foregoing, a positive/negative list (department-wise) of such information which can/cannot be disclosed either wholly or partially can be prepared which could be only indicative and not exhaustive and is subject to review/revision. While drawing up such a list, the principle to be adhered to is that only such information as would qualify under the exemptions of the RTI –those exemptions (Sec. 8&9) related to commercial confidentiality and national security, strategic, scientific or economic interests of the State, privacy, investigations or law enforcement, and information covered by legal privilege etc should be classified..

The National Data Sharing and Accessibility Policy (NDSAP)-2012 promotes proactive disclosure mechanisms to make all sharable and reliable information available to the public for scientific, economic and social developmental purposes, subject to legal conformity, protection of intellectual property, formal responsibility, professionalism, standards, interoperability, quality, security, efficiency, accountability, sustainability and privacy.

The negative list under the NDSAP contains all non-sharable data as declared by the departments/ organisations including restricted data (need-to-know on authorisation) and sensitive data as defined in various Acts and rules of the Government of India. This may serve as a precursor requiring far more legal scrutiny and consideration of the public interest, while formulating a comprehensive information disclosure policy. (The writer is Consultant-Law at Centre for Good Governance, Hyderabad)