Will movie theaters disappear!?

When I was a child, people would come trekking from villages to towns in long lines to watch films like “Lavakusha”— afterward they would feel their lives had been blessed. Even now, those who have experienced those days recall those stories like legends.

For the common person back then, a simple unreserved ground ticket was enough to see a movie. Today, people watch in multiplexes by procuring tickets in-black, and they spend far more — buying expensive popcorn and snacks there, and paying many times over what they would have paid at home. Movies of that era mixed the nine emotions with small, easily understood moral messages that the public could put into practice. Producers did make films to earn money, but they weren’t driven by a blind desire to extract every last rupee the way some are today — the producers, directors and actors then didn’t behave solely for profit. Along with entertainment, those films imparted lasting memories and taught audiences how to tell right from wrong. Family dramas, the heroic adventures of folk leaders, villains who showed cruelty only to meet their just end at the hands of the hero, mythological tales — these films were made in a way that people would keep calendars featuring actors who acted as Krishna and Rama on their household altars.

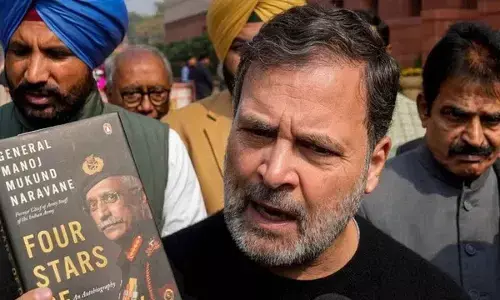

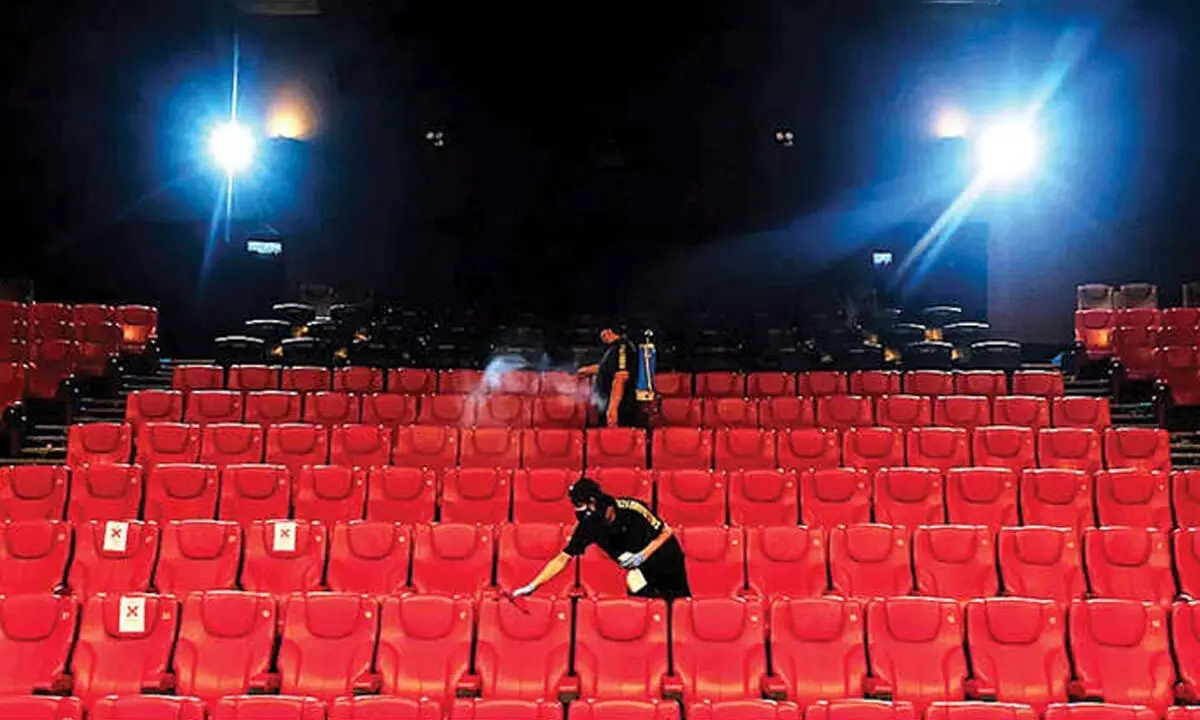

Even if one or two “class” films are made with the producers’ ambitions, they often rely on government help and awards to break even or take a small loss! There’s no need to spell out today’s film-making practices, audience quirks, the needless fuss fans create, the rowdy incidents or the law-and-order problems. Even for a celebrated film, when a viewer struggles to sit through a two-and-a-half-hour movie, it’s inevitable to ask whether films are gradually becoming distant from the average person — and who is responsible for this situation? Ordinary single-screen theaters are dying with the arrival of multiplexes. In some towns the cinema halls have been turned into function halls. Watching films at home on an OTT service feels just like TV. Who will bring those viewers back into cinema halls to watch films again? Filmmakers and studio heads in our country are content simply by looking at box-office numbers. In their obsession with making pan-India blockbusters, they’ve abandoned the idea that ordinary films can still be made entertainingly. Actors and directors can become billionaires after one or two hits, can’t they? In the delusion that films are just a source of money, they have long forgotten the average viewer.

Our cinema has reached a point where we must protect it, just like we protect our language! A film meant for entertainment should not leave audiences financially ruined. For producers, directors and actors to change Indian cinema into something like unreachable grapes is a petty betrayal! Those who rob ordinary people—who spend their leisure and hard-earned money by the basketful—of their only available source of amusement, no matter how celebrated or praised as artistic geniuses, are worthy of condemnation and must face strong censure. Even in Western countries, books fell out of favour for a time and were neglected under the shadow of television. But now they are once again regaining the popularity, readers and knowledge they had lost.

Netflix-Warner’s deal is shaking Hollywood to the core, even raising questions about the future of films. People are now debating whether the Hollywood system that used to craft real, substantive movies is coming apart. Once this deal goes through, the kind of films audiences want could disappear into the sands of time. Independently-minded, artistically-driven films will struggle to stay afloat. Average moviegoers are already noticing and feeling disappointed by the changing situation. Companies like Paramount are strongly opposing the deal. Will theaters — once the go-to place for movie fans — become unavailable? Even U.S. President Donald Trump has warned that this deal could be dangerous for movie audiences. Courts and experts are looking at legal options and considering how to resolve the issue amicably and acceptably. Here too, it’s only natural that intellectuals, social activists and policymakers — concerned about the interests of filmgoers — are coming together in hopes of keeping cinema accessible to the public.

(The writer is a retired IPS officer, who has served as an Additional DGP of Andhra Pradesh)