Secular and Socialist: A Constitutional debate beyond words

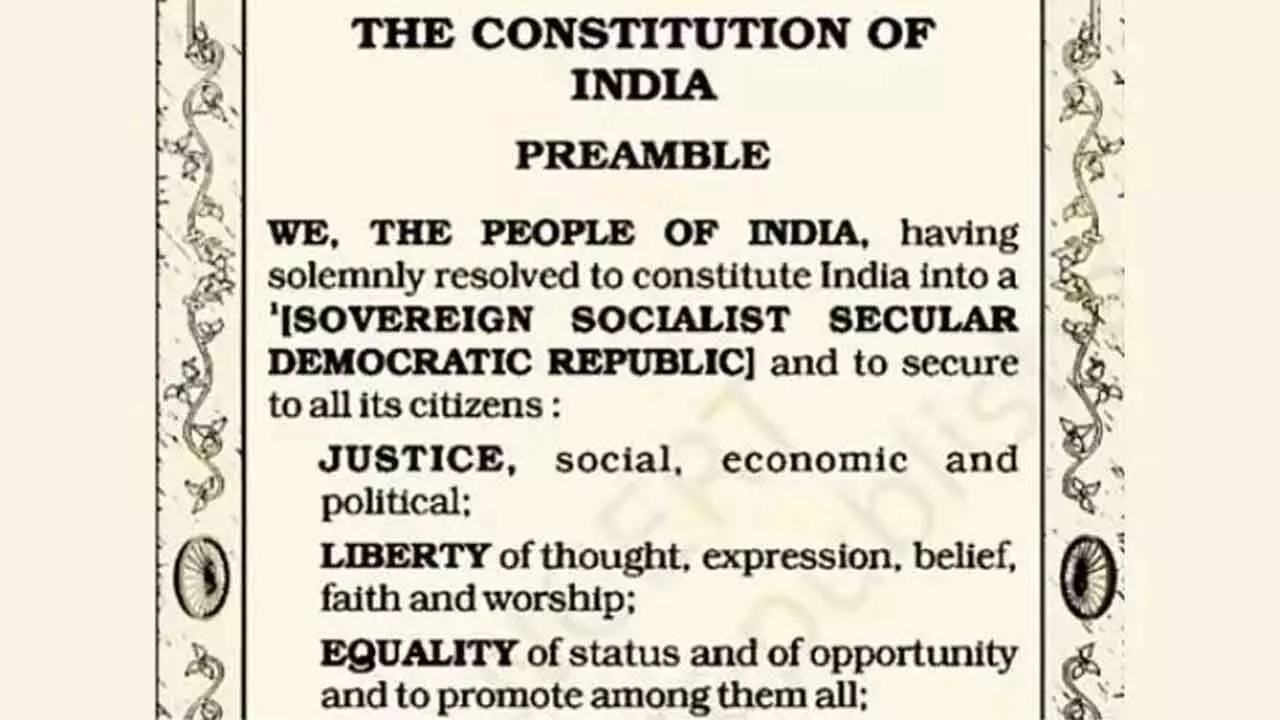

These words, conspicuously absent when the Constitution was adopted in 1950, were introduced through the 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act of 1976, during the national emergency. The manner and timing of their inclusion have sparked persistent questions about their necessity, legitimacy and impact on the foundational spirit of the Republic. This debate is not merely about words but reflects a deeper struggle over India’s identity and the delicate balance between historical intent and evolving aspirations.

On June 25, 1975, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi invoked Article 352, declaring a state of emergency citing “internal disturbance.” This unprecedented move, which lasted until March 21, 1977, curtailed civil liberties, suppressed political opposition, and placed the legislative process under extraordinary strain.

It was during this turbulent period that the 42nd Amendment, often termed the ‘mini-Constitution’, added ‘secular’ and ‘socialist’ to the Preamble. Critics argue that the emergency’s restrictive environment, which stifled democratic discourse, undermined the legitimacy of this change. The decision to insert these terms appears disconnected from the emergency’s stated purpose, suggesting an attempt to imbue the Constitution with a specific ideological bent rather than a reflection of broad national consensus.

The Constituent Assembly, which meticulously crafted the original Constitution, had deliberately chosen not to include these terms after exhaustive debates. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Constitution’s chief architect, emphasized that principles like religious neutrality and social justice were already woven into the document’s fabric, particularly through the Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles of State Policy.

The Assembly believed that explicit labels in the Preamble were unnecessary, as the Constitution’s ethos already embodied these values. The 1976 amendment, therefore, raises a critical question: if these principles were inherent, why were they added during a period of curtailed democratic processes? Some view the move as an effort to legitimize the emergency regime’s actions by aligning the Constitution with the ruling government’s ideology, rather than a genuine expression of national will.

The Supreme Court has played a pivotal role in interpreting these terms, affirming their constitutional validity while clarifying their meaning in the Indian context.

Indian secularism, distinct from the Western model of strict separation between state and religion, embodies the principle of equal respect for all faiths, often described as Sarva Dharma Sambhava. The state maintains neutrality, neither favoring nor discriminating against any religion, while ensuring religious freedom for all citizens.

In the landmark S.R. Bommai v. Union of India (1994) case, a nine-judge bench declared secularism a basic feature of the Constitution, unalterable even by amendment. The Court emphasized that religion is a matter of individual faith and cannot be mixed with secular activities, reinforcing the state’s role as a neutral arbiter. This ruling underscored that secularism was intrinsic to the Constitution, even before its explicit inclusion, validating the 42nd Amendment’s addition of the term. Subsequent judgments have consistently reaffirmed secularism’s centrality, positioning it as a guiding principle for state action and policy in India’s diverse society.

Similarly, the term ‘socialist’ in the Indian context denotes a commitment to social and economic justice, rather than rigid state control of production.

Described as “democratic socialism”, it seeks to reduce inequalities and ensure a decent standard of living through democratic means. The Supreme Court has linked socialism to the Directive Principles, particularly those aiming to promote welfare and minimise disparities. In one judgment, the apex court observed that a socialist state’s primary aim is to eliminate inequality in income, status, and standard of life. This interpretation envisions a mixed economy where the state intervenes to protect the vulnerable and ensure equitable resource distribution. The judiciary’s endorsement has largely settled the legal standing of these terms, but it has not fully resolved the philosophical and historical debates surrounding their inclusion, particularly given their perceived redundancy considering the Constitution’s existing provisions.

The retention of ‘secular’ and ‘socialist’ in the Preamble, even after the 44th Amendment of 1977 reversed many of the 42nd Amendment’s changes, underscores their symbolic importance. Proponents argue that these terms serve as a constant reminder of India’s commitment to pluralism and social justice, particularly in a nation grappling with communal tensions and economic disparities. Their presence is seen as prescriptive, guiding India toward an inclusive and equitable future. Conversely, critics contend that the terms are superfluous, as their principles are already enshrined in the Constitution’s substantive provisions. They argue that removing these words would not alter the Constitution’s fabric, as the judiciary has affirmed that secularism and socialism are intrinsic to its basic structure. Such a move, they suggest, would honour the Constituent Assembly’s original intent, which prioritized substance over symbolic labels. The Assembly’s decision to omit these terms was not an oversight but a deliberate choice, reflecting confidence that the Constitution’s provisions adequately embodied these ideals.

The debate also raises questions about the 42nd Amendment’s political motivations. Critics view it as an attempt to consolidate power during the emergency, while the selective retention of these terms during the 44th Amendment suggests a complex interplay of political will and recognition of their symbolic value.

If a proposal were made to remove these terms without altering other constitutional provisions, opposition would likely stem from their symbolic weight rather than their substantive impact. Their deletion could be misinterpreted as a retreat from India’s pluralistic and welfare-oriented ethos, potentially emboldening divisive forces.

However, proponents of its removal argue that such an act would reaffirm the Constituent Assembly’s wisdom, prioritising the Constitution’s implicit strength over explicit labels.

This debate reflects a broader struggle over India’s constitutional identity. The Preamble is not merely a preface but a living testament to the nation’s aspirations. Whether these terms remain or are removed, the principles they represent—secularism as a commitment to harmony and socialism as a pursuit of equity—will continue to shape India’s democratic journey.

The judiciary’s affirmation of these principles as part of the Constitution’s basic structure provides a robust legal foundation, yet the philosophical and political discourse remains vibrant.

As India navigates its future, the challenge lies in balancing respect for the Constitution’s historical intent with the evolving needs of a diverse, dynamic democracy.

The question is not just about words but about the enduring vision for a nation committed to justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity for all its citizens.

(The writer is a senior Advocate)