Renewable energy: Is wind losing ground?

India installed 62 per cent of the targeted capacity of 60 gigawatt (GW) of wind power by 2015, according to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE).

India installed 62 per cent of the targeted capacity of 60 gigawatt (GW) of wind power by 2015, according to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE). Installing the remaining capacity, however, will be challenging as the inception of new wind power projects remains difficult.

It's a vicious cycle: Operational challenges put existing projects in a spot, created financial risks and reduced liquidity. This, in turn, reduces prospects of the sector and puts a question mark on the target's achievability.

Wind projects require characterisation of the site and data collection for the long-term, the onus of which has been on developers. They, however, are not facilitated to create projects in different States — with different geographies and wind speeds.

This limits growth to select regions. Risks to emerging projects increase costs, while States and distribution companies (discoms) expect the lowest-possible tariffs. This persistent disconnect discourages developers from participating in new tenders.

Tariff caps have resulted in under-subscribed auctions, reduced allocations and cancellations of awarded contracts. Not a single auction in 2019-2020 was fully subscribed to; the total response recorded was 45 per cent.

The latest bids invited in September 2019 to develop 1,200 megawatts (MW) of wind power projects under Tranche-IX of the Inter-State Transmission System (ISTS) programme received negligible response. The Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) had to increase tariff caps to Rs 2.93 per kilowatthour (kWh) from Rs 2.85 / kWh. Despite that, it had to postpone the auction for the fourth time.

"As long as the prices obtained from the wind power auction are significantly lower than the National Average Power Purchase Cost, new wind projects should be encouraged. If such projects are not encouraged, it will cause under-utilisation of a natural resource especially when the whole supply chain is ready and is indigenous," said Manish K Singh, Secretary-General, Indian Wind Energy Association.

Competition prompts independent power producers (IPP) to quote low tariffs with the expectation of accessing cheap and windy land. But increasing demand for good sites raises prices, making projects unviable.

"Those who have wind sites have gone bankrupt while the ones with funds do not have sites," said Sunil Jain, chief executive officer and executive director, Hero Futures Energy. This has created a virtual unavailability of land, leading to delays in projects.

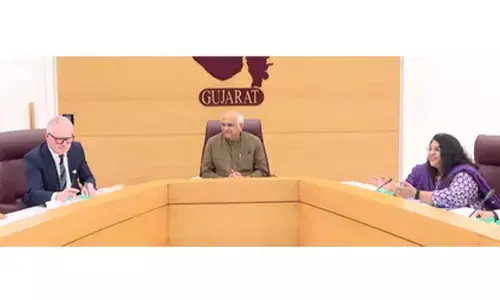

Projects in two of the windiest States — Gujarat and Tamil Nadu — are now viable only at imposed tariff caps. This limits the availability of sites and leads to imbalanced growth.

Gujarat is reluctant to provide its best wind sites for projects worth about 5GW that will serve other States. Tamil Nadu, on the other hand, is not prepared to add more wind capacity as it is already struggling to use power from existing renewable energy projects, which enjoy a must-run status.

"All good land sites being taken up is a fallacious argument. Projects can be developed if the different wind sites are properly characterised. It may not give the lowest price but may result in a balanced growth," said Balwant Joshi, Managing Director at Idam Infrastructure Advisory Pvt Ltd.

The government needs to pursue an alternative approach. Potential to generate wind energy in other States can easily be tapped with newer technologies capable of generating power at lower wind speed, increasing the capacity utilisation factor (CUF). Every wind site is characteristically different. Hence, the same mechanism cannot be applied to all.

The timely construction of evacuation facilities and adequate availability networks for integration of renewable energy to the grid has been pending for long. Transmission capacity has grown 6.5 per cent annually during 2015-16-2018-19; renewable energy has increased at more than 20 per cent in the same period.

The 160 MW solar-wind hybrid project in Andhra Pradesh has been delayed on account of land acquisition and clarity on the transmission system.

Other major risks include payment delays and mounting dues and curtailment of generated power by state utilities.

Thus, state tenders do not draw responses. The trend is also worsening for SECI auctions.

Credit rating agency ICRA Ltd in October 2019 revised its outlook for nearly a third of its wind and solar power portfolio in terms of installed capacity. It cited a "gradual deterioration in the liquidity profile of the IPPs due to payment delays from a few State distribution utilities (discoms)" as a major reason.

By the end of the year, it downgraded the entire sector in India to 'negative' due to presistent delays in payments from discoms and execution of projects.

Andhra Pradesh recently pulled off significant incentives — wheeling charges, banking facilities and procurement of government land — from renewable energy generators, including wind and hybrid. Such instances create uncertainties and endanger future growth.

Open access rules have been tweaked by regulatory commissions over a period: Earlier, charges were based on the number of units, while now they are based on 'per month / kW' on the long term. This makes earlier business models unviable.

At 20-40 per cent of CUF, such charges have become exorbitant.

"The decision to re-negotiate PPAs signed between utilities of the government of Andhra Pradesh and solar/wind power developers has shaken the confidence of investors in the sector, adversely impacting growth of the sector," RK Singh, Minister of State with Independent Charge at the Union Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, told the Lok Sabha .

India's aspiration to become a global solar energy power has affected the wind power sector.

Tariffs for wind power are currently similar to those of solar power. But there are questions about sustainability. Wind's long-term competitiveness vis-à-vis solar may weaken if costs in the solar sector drop faster as the best wind sites are taken up.

Indeed, the country's plans call for a far smaller capacity of wind compared to solar.

"Wind and solar are two different technologies and should be treated differently.

The government should help the equitable development of all resources. If the aim of the government is to procure the cheapest power then there should be no capacity demarcation within 175 GW of renewable energy. But if 60 GW is required from wind, then it should be treated appropriately," said Joshi.

Unlike solar, wind power development cost varies state to State. The government should come to develop projects, collect data and then carry out biddings. Instead, it calls for bids anywhere in India on a competitive basis with ceiling prices, resulting in lop-sided development.

Due to high variability, wind projects face a higher risk of curtailment putting them at a disadvantageous place with respect to solar projects. On the contrary, the wind sector is often deprived of support which the solar sector is given.

In fact, development of wind parks (similar to solar parks), where the government takes care of the land and integration of power to the grid — two difficult challenges — is entirely missing for the wind sector. These issues are more important for the sector as wind projects are viable in two States only.

The government's treatment towards the wind sector in the backdrop of a roaring solar industry and single-minded focus on tariffs without considering technicalities has caused a slowdown. Many producers have shut down, finding it difficult to sustain.

Due to the capricious nature of wind, power generation is highly variable and seasonal. It is difficult to predict generation at a given time of the day. This also leads to higher curtailment.

But wind energy brings distinct value to the overall energy mix as it is available during peak-demand time in the evening (7pm-10 pm), unlike solar. On the other hand, wind energy generation is the highest from June to October in Tamil Nadu and August to September in Gujarat, when demand tends to slow.

Forecasting and scheduling for wind generation is more difficult because of its highly variable nature. Therefore it is important to incorporate better forecasting technologies — statistical tools, online measurements and satellite data.

Recent changes in deviation settlement mechanism on a 15-minute basis make it unviable for small individual 1 MW size plants compared to a 100 MW plant as it is difficult to predict for smaller plants. Therefore, new projects hardly come up under open-access modes.

(Courtesy: Down To Earth)