Removing ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ from the Preamble is a constitutional conspiracy

Similarly, omitting “socialist” may not erase the Directive Principles that form the Constitution’s moral compass. But it weakens the interpretative commitment to social justice. Removing this term could shift judicial interpretation towards a market-centric reading of rights and minimise the State’s duty to reduce inequalities of wealth and opportunity. In a country where poverty, caste barriers, and structural exclusion still shape lived reality, such a shift would have profound consequences.

Any attempt to amend the Constitution through the “private amendment power” without discussion, debate, or public consultation strikes at the heart of parliamentary democracy. A Constitution is not an ordinary statute; it is the foundational charter of a nation. It could be a ‘constitutional conspiracy’ to try to alter its character, especially its Preamble, which demands the highest standards of transparency, deliberation, and consensus. Rushing such an amendment through Parliament, without giving Members time to analyse its implications or allowing citizens, experts, and civil society to voice their views, is not merely procedurally flawed—it is fundamentally undemocratic.

The Constituent Assembly spent nearly three years debating every word of the Constitution. To now alter its core ideas without meaningful deliberation diminishes both the dignity of Parliament and erodes people’s trust. Constitutional change cannot be manufactured in secrecy or political haste; it must be earned through open, reasoned, democratic engagement.

Bill title is erroneous:

Interestingly, the name of the Bill is ‘establishment of the National Committee for Protection of Media Persons’. It is claimed to ensure effective prevention of violence in cases related to arbitrary censorship, intimidation, assault, or risk to the free speech of the media. This raises many doubts as to free speech of the media, because there is no relevance or purpose to serve what is being claimed. It may totally affect the basic structure of our rule of law.

The Constitution (Amendment) Bill, 2025, seeking to delete the words “socialist” and “secular” from the Preamble, is far more than a textual modification. It challenges the very identity of the Indian Republic that has evolved over seven decades.

Supporters of the Bill argue that these terms were inserted during the Emergency through an undemocratic process, without debate or opposition, and therefore lack moral legitimacy. But that argument must be weighed against the constitutional, judicial, and political developments since 1976, and the implications of such a drastic rollback today?

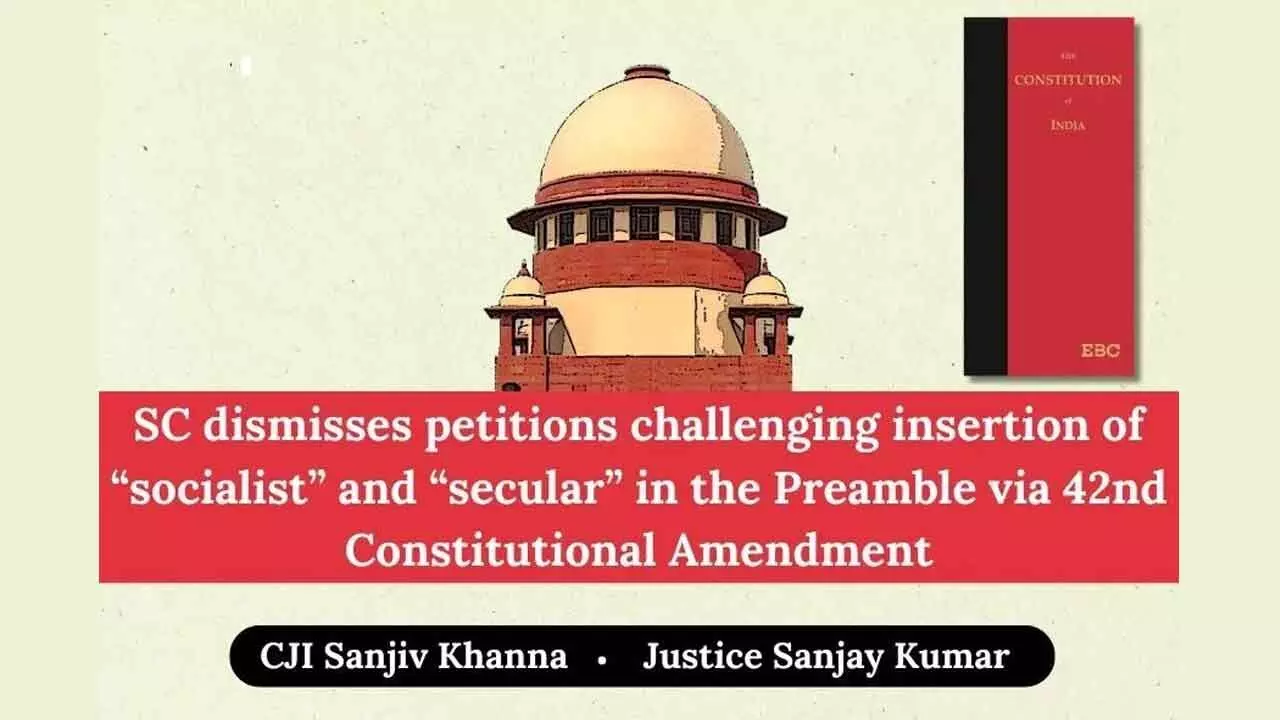

The 42nd Amendment was indeed enacted under extraordinary circumstances. The opposition was suppressed, democratic institutions were weakened, and civil liberties were suspended. Yet, whether an amendment was enacted during an Emergency does not, by itself, render it unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld the validity of the amended Preamble—not once, but across decades and several landmark judgments. By affirming secularism and socialism as elements of the basic structure, the judiciary has woven these concepts deeply into our constitutional fabric.

This brings us to the first and most important question: Can Parliament delete principles that the Supreme Court has declared part of the basic structure?

Under the Kesavananda Bharati doctrine, Parliament cannot alter the core identity of the Constitution. Secularism was upheld as a fundamental feature in 1973, three years before it was inserted into the Preamble. The court reasoned that Articles 14, 15, 25 to 30, and 51A form a secular framework regardless of the word’s presence. Removing the word now may create uncertainty about the character of the Indian State, inviting a constitutional confrontation between Parliament and the judiciary.

A western concept!

The argument that “secularism is a western concept” ignores the fact that the Indian model—best described by the phrase Sarva Dharma Samabhava—has always been distinct from the Western separation-of-church-and-state doctrine. Indian secularism does not insist on a religion-free State; it insists on equal respect, non-discrimination, and neutrality.

Without the word “secular” anchoring judicial interpretation, such protections could be eroded by majoritarian policymaking or selective State patronage of religion.

Similarly, omitting “socialist” may not erase the Directive Principles that form the Constitution’s moral compass. But it weakens the interpretative commitment to social justice. The Indian socialist framework was never about Marxist state control; it was about balancing economic liberties with welfare obligations. Removing this term could shift judicial interpretation towards a market-centric reading of rights and minimise the State’s duty to reduce inequalities of wealth and opportunity. In a country where poverty, caste barriers, and structural exclusion still shape lived reality, such a shift would have profound consequences.

Critics of the socialist ethos often blame it for bureaucratic inefficiency, corruption, and a subsidy culture. But these are failures of governance, not constitutional philosophy. Removing the word will not magically produce innovation or competition; it may instead dilute the moral imperative behind welfare schemes, affirmative action, labour protections, and equitable resource distribution.

The Bill argues that the original Preamble, adopted in 1949, did not contain these terms, and therefore removing them “restores” the founding vision. But constitutions are not museum artefacts. They grow, evolve, and respond to historical needs. The 2025 India is vastly different from the India in 1949. Reverting to a pre-1976 text is not restoration; it is reinterpretation—one that aligns more with the ideological preferences of the present political majority than with any compelling constitutional necessity.

Most critically, this amendment challenges the delicate balance between Parliament and the Supreme Court. By inviting the court to reconsider whether principles added through an “undemocratic” amendment can still be part of the basic structure, parliament is asserting its supremacy. But constitutional democracy is built on shared power, not unilateral assertion. Removing the textual guarantee of secularism and socialism will alter the spirit of the Republic without amending the provisions, which actually guarantee freedom of religion, equality, and welfare.

India’s constitutional journey has been marked by a commitment to pluralism, justice, and human dignity. The proposed amendment, instead of strengthening that journey, pulls the nation into an avoidable ideological battle. Whether or not the Supreme Court eventually intervenes, the political message is unmistakable: the identity of the Republic is up for renegotiation. As the debate unfolds, one hopes that Parliament will recall that the Constitution is not only a legal document but a moral one—born from the collective aspirations of a diverse people. Any change to its guiding principles must be anchored in consensus, caution, and constitutional conscience.

(The writer is a ormer Central Information Commissioner, and presently Professor, School of Law, Mahindra University, Hyderabad)