Looking at crime and punishment

Looking at crime and punishment

The International Criminal Court (ICC or ICCt) is an inter-governmental organisation, a tribunal with its headquarters in Hague, Netherlands

The International Criminal Court (ICC or ICCt) is an inter-governmental organisation, a tribunal with its headquarters in Hague, Netherlands. The ICC is the first and only permanent international Court with jurisdiction to prosecute individuals for international crimes such as genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and aggression. It aims to complement existing national judicial systems and exercises jurisdiction only in situations when national courts are unwilling, or unable, to prosecute criminals.

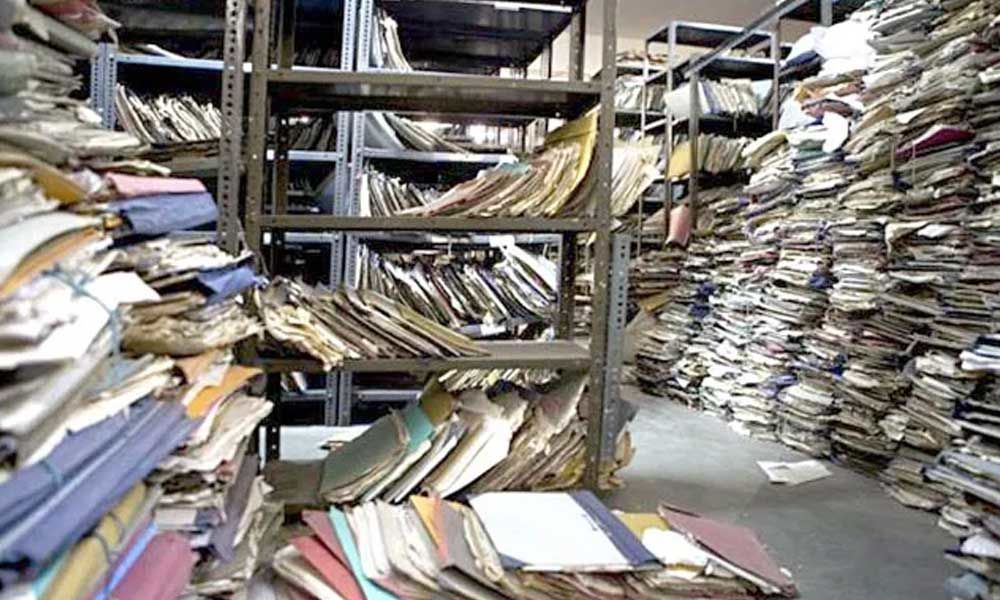

Computerisation of court administration in India began about two decades ago, with the government of India (GoI) taking the initiative. That step has paid rich dividends, cost and time wise. As the common people can also access the information, the system has increased the confidence reposed by them in the judicial system. The benefit is, however, yet to spread to the rural areas of the country, account of poor internet connectivity, ignorance about the operation of electronic gadgets and also lack of awareness.

Increasing the penetration of internet services and arranging for greater availability of computers and mobile phones, together with a programme of awareness generation, will ensure the inclusion of those areas also into the coverage of the programme.

The government of India has taken proactive steps such as the establishment of the computerisation and computer networking of Consumer Fora (CONFONAT) to strengthen consumerism. The Fora have played a significant role, particularly in the area of consumer protection. Their services, being information technology enabled, have paved the way for the dispensation of justice in a speedy and effective manner.

In 1990, the National Informatics Centre (of the Ministry of Information Technology, Government of India), started the process of computerisation in the Supreme Court. As a result, many applications have been computerised which have had a positive providing relief to litigants. Similar computerisation is also in place at 18 High Courts of the country.

The Indian judiciary is taking steps to apply e-commerce for efficient management of its work. In the near future all the courts in India will be computerised in that respect, and new judges who are being appointed will be expected to have basic knowledge of the computer operation.

Among the most important issues that attracted my attention, during my tenure as the Chief Secretary, Government of Andhra Pradesh, was the huge pendency of civil and criminal cases in the High Court and subordinate Courts. Alarmed by the situation, the Advocate General (AG) and I set about trying to computerise the entire information with regards to pending cases, especially those involving the government as a party.

Part of the attempt comprised an A, B, C classification of pending cases. The A category consisted of cases which required immediate attention either in terms of the amount of public money involved or other reasons such as the possibility of imminent criminal proceedings being launched against a government servant etc. The C category comprised trivial and petty matters, about which the AG and I felt that summary disposal should be requested, without bothering too much about the way the verdict went.

The middle category, namely B, we felt, could safely be left to the system to handle, as neither in terms of importance, not in terms of number, did that category demand immediate attention. As a result, it was expected that, both in terms of attention being paid to matters requiring immediate action, and securing satisfactory disposal of cases in terms of numbers, substantial progress could be achieved in a short while.

What we need to understand clearly is the fact that, just as morality does and every code of ethics does, the concepts of crime and punishment were, are, and will be functions of time and space, subject to variations which can, sometimes, even be significant.

Take, for instance, the question of abortion. While it is now legal in India, it was a crime until recently, in countries where the laws in force were influenced by the philosophy of the Catholic sect of Christian religion. While the UK legalised abortion in 1967, Northern Ireland followed suit as recently as in 2020.

On somewhat similar lines, the Catholic sect of Christian religion, while permitting divorce to take place, prohibits remarriage. The practice of slavery, for instance, was legal until the 19th century, in the United States. And, even today, there are those who nurture the feeling that black – on black crime attracts much little less attention in that country then even such a minor thing as the disappearance of a white teenager. To cite another example, the notorious criminal Jack the Ripper, was believed to have been allowed to remain on the loose, as the London police force could not believe that a 'gentleman' could commit crimes.

The much talked about nexus, between criminals, political leaders, businessmen and civil servants has, for long, threatened to shake the foundations of the edifice of governance in India. So much so, that, in the year 1993, the government of India appointed the Vohra Committee to look into the matter. The Committee highlighted the nexus between the criminals, politicians and government functionaries.

It also stated that the network of the mafia was virtually running a parallel government, pushing the State apparatus to irrelevance. The Committee made various important recommendations, including a suggestion that an institution be set up to effectively deal with the menace, following which many steps have since been taken to deal with the menace of the nexus. That is not to say, however, that the problem has gone away.

However, given the strong foundations on which the three wings of State in our country rest, one hopes that clean politics, sound governance and a free and impartial system of justice will soon prevail over forces that threaten to undermine the strength and character of our institutions and seek to compromise their integrity.

Clearly, there is immediate need to decriminalise politics and bring about a range of reforms in the criminal justice system, including police reforms. Before we conclude this discussion, it is necessary for us to remember that, no matter what other criticism may be levelled against the British, and their rule, they did leave behind a sound and robust justice system, whether criminal or civil.

That system not only answered to the demands of the times when it was established, but has also shown that it possesses the inbuilt resilience, and flexibility, needed to respond to the varying demands, over time and space, made on it by a vast and diverse country such as ours.

And the democratic system of governance we have chosen, with the edifice of the State resting on the firm tripod of the executive, judiciary and the legislature wings, has also come of age, with the three wings learning to coexist in an atmosphere informed by a spirit of harmony, coordination and mutual respect. The problems we have discussed earlier, therefore, can safely be expected to be resolved effectively, and soon.

Purely in a lighter vein, I must here recall the words of a Very Very Important Person who, while inaugurating the functioning of a newly constituted High Court, following the formation of a new state, expressed the hope that, from then on, justice would be speedily "dispensed with!".

(The writer is former Chief Secretary, Government of Andhra Pradesh)