Dr Raju’s 1980 vision for a tribal university that India forgot

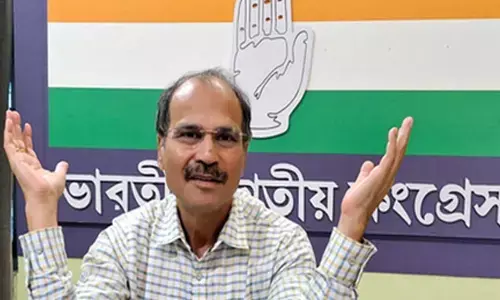

1965- Vizag airport- Indira Gandhi being received by PVG Raju

History is often shaped not only by what nations achieve, but also by the dreams that remain unfulfilled; dreams that reveal the depth of human generosity and visionary leadership.

Among such forgotten chapters lies a remarkable moment from April 3, 1980, when the last Maharaja of Vizianagaram, Dr Pusapati Vijayarama Gajapathi Raju (P V G Raju)—scholar, philanthropist, parliamentarian, and the guiding soul of MANSAS—wrote an extraordinary letter to then prime minister Indira Gandhi. In that letter, he offered to donate more than 3,600 acres of his ancestral land for establishing a national-level Tribal University, decades before the Indian government even began discussing higher education for tribal communities on a national scale.

The letter, preserved today as a treasured document, stands as a testament to his foresight and the benevolent spirit of the Pusapati dynasty—a family whose contribution to education and culture in northern Andhra Pradesh spans centuries.

What makes this gesture exceptional is not merely the size of the land he offered, but the intent behind it. At a time when tribal welfare was hardly part of mainstream conversation, Dr Raju imagined a modern, multidisciplinary university dedicated entirely to tribal knowledge systems, development, agricultural innovation, arts, and inclusive education. His dream, conceived nearly half a century ago, remains astonishingly relevant to contemporary India.

In his letter, he specifically identified two tribal villages—Peakararajuvvalasa and Kerangi—located in the serene, forested hills near Salur. These were not random selections. He described them with meticulous detail: Kerangi stood at an elevation of 2,380 feet, spread across more than 2,300 acres, while the adjoining village offered another 1,338 acres. Together, this impressive expanse formed a continuous belt of over 3,600 acres, perfectly suited for establishing a university campus, research farms, laboratories, tribal museums, and residential facilities.

His reasoning was as strategic as it was humane. These villages were geographically positioned at the tri-junction of Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, and Madhya Pradesh. As he wrote, the region “can become the basic centre” for tribal development, given its centrality to three major tribal belts. In other words, he envisioned a university that would not merely serve one state but would uplift the entire tribal populations across eastern and central India. This was not just land—it was an investment in India’s most underserved communities, offered with no expectation of return.

Yet, despite the clarity of his proposal and the magnitude of his generosity, the dream went unfulfilled. Perhaps it was the political climate of the time, perhaps bureaucratic silence, or perhaps the magnitude of the idea. Whatever the reason, India lost an opportunity to establish one of the earliest tribal universities in the world—years before similar models emerged elsewhere.

But to understand the depth of this gesture, one must also understand the legacy of MANSAS—the Maharaja Alak Narayana Society of Arts and Science, founded in 1958 by Dr Raju in memory of his father. Even before he penned this letter, the Maharaja had already dedicated vast stretches of his estate to educational institutions. The crown jewel among them was the illustrious M R College, established in 1857–58. It was the second oldest degree college in the entire Madras Presidency, preceded only by the famed Presidency College in Chennai. For generations, it stood as the intellectual heart of the region, producing administrators, scholars, judges, scientists, and writers who shaped the cultural and civic landscape of Andhra.

By 1980, MANSAS had grown into an educational ecosystem unmatched by any other private trust in the region. It included the M R. College for Women, one of the earliest women’s colleges in coastal Andhra; the M R College of Education, dedicated to teacher training; the iconic M R Girls High School; the progressive Model High School; and the English and Telugu medium schools established during the 1970s.

Thousands of young boys and girls from Vizianagaram, Bobbili, Salur, Parvathipuram, and surrounding tribal mandals found their future inside these classrooms. Unlike many princely families, who resisted land reforms, the Pusapati rulers consistently channelled their resources into public welfare, long after losing their administrative authority.

Dr Raju’s personal philosophy was rooted in an unwavering belief that true legacy lies not in palaces or titles, but in institutions that serve society. Even after losing control of his estate during the abolition of the zamindari system, he continued to give away what remained—often in silence, often without acknowledgement. His 1980 letter captures this spirit in every line. He writes not as a former ruler seeking recognition, but as a citizen deeply committed to the upliftment of marginalized communities.

He suggests that a special central dispensation be created for the university, recognizing that tribal education required a different administrative and academic framework from conventional institutions.

In today’s language, he was asking for an autonomous national institute—decades before similar models like Tribal Research Institutes or the Central Tribal University of Andhra Pradesh were even conceived.

Reading the letter now, one cannot help but feel a gentle ache; a sense of what might have been. Had the university been established in the early 1980s, it might have transformed the tribal landscape of Andhra, Odisha, and Madhya Pradesh. It could have become a pioneering centre for agriculture suited to tribal lands, for indigenous knowledge systems, for tribal languages, for forest sciences, and for economic empowerment. The 3,600-acre campus might have grown into one of India’s most iconic educational hubs—born not from any government initiative but from the magnanimity of a Maharaja who believed education was the greatest gift.

Today, as the nation speaks about inclusive development, tribal welfare, and educational equity, Dr Raju’s letter feels prophetic. It reminds us that visionary leadership is timeless, and that sometimes, the most transformative ideas are the ones waiting patiently on paper, hoping for a second chance. Perhaps the time has come for the government and policy makers to reopen this historic proposal and honor the Maharaja’s extraordinary spirit of service.

(The writer is a former OSD to the former Union Civil Aviation Minister)