Aravallis face an uncertain future, but Parliament remains silent

India’s oldest mountains didn’t matter to Parliament

Another Winter Session ends as a costly exercise in disruption, exposing Parliament’s steady slide from deliberation to drama. Despite a limited agenda, sloganeering, walkouts and adjournments eclipsed law-making, scrutiny and accountability, squandering over Rs 200 crore of taxpayers’ money. More alarming was Parliament’s silence on two existential crises—toxic pollution and the imminent dismantling of the Aravalli range through a dubious technical redefinition. As MPs traded rhetoric, India’s oldest ecological shield faced erasure, threatening water security, climate stability and public health. This failure of seriousness and conscience raises a stark question: who will defend the people and the nation if Parliament will not?

Another winter session of Parliament has slipped away—not with the dignity of robust debate or the satisfaction of legislative achievement, but amid disruption, adjournments and political brinkmanship. Though marginally better than earlier sessions, with some discussions taking place, what ultimately unfolded—sloganeering, walkouts and repeated forced adjournments—only reaffirmed a grim reality: disruption has become the norm, and the Parliament increasingly resembles a theatre rather than a forum for delivery.

The winter session discussed issues such as Vande Mataram, electoral reforms, including SIR, and G-RAM G, but these were sporadic and superficial. Across party lines, members showed lack of seriousness. The dominant pattern was predictable—raise a demand, insist on a debate on one’s own terms, and then stage a walkout. The outcome remains depressingly familiar.

The Houses could barely transact business. Legislative scrutiny suffered. Private members’ business was marginalised. Policy discussions were repeatedly sacrificed at the altar of partisan posturing. What was lost was not merely time, but the very purpose of parliamentary democracy.

Parliament is not a protest site; it is the central forum of India’s constitutional democracy. When members deliberately stall proceedings, they are denying citizens their right to representation. Every hour lost belongs not to the treasury benches or the opposition, but to the people who elected these representatives to deliberate, legislate and hold power to account. It is also the taxpayer’s hard-earned money that is being squandered. A 15-day session costs the exchequer well over ₹200 crore. No democracy can afford such irresponsibility.

The time has perhaps come for a serious national debate on accountability mechanisms, including the idea of a right to recall for non-performing legislators. Members who demand accountability from every institution must first learn to be accountable to the people. Citizens are no longer interested in noise, theatrics and manufactured outrage—inside or outside Parliament. What they expect is seriousness, outcomes and governance.

The tragedy is that the Parliament has abdicated its responsibility. The real tragedy is not just what was left undone, but what is steadily being unlearned—the habit of dialogue, disagreement and democratic discipline. If this decline continues, the cost will be paid not merely by politicians, but by the country itself.

More disturbingly, Parliament failed to meaningfully engage with two critical issues that have potentially devastating consequences for the people of India.

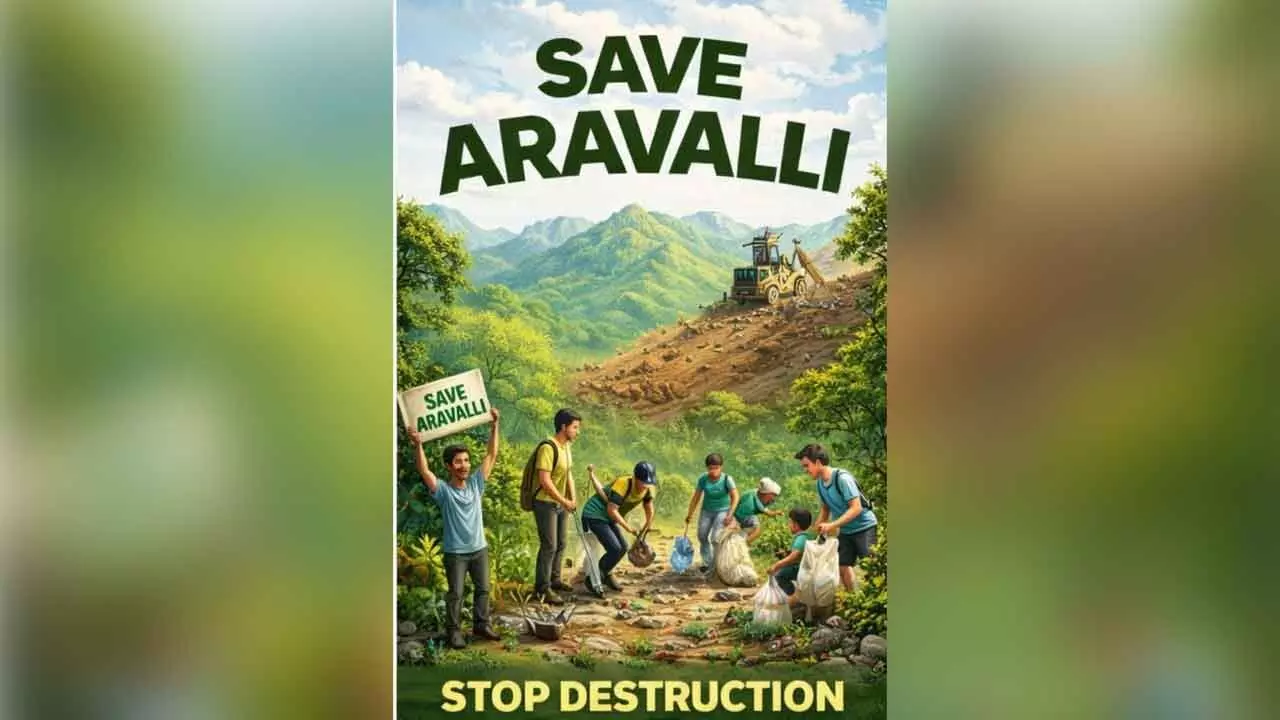

The first is the dangerously high pollution levels in Delhi and several other states, posing a severe public health emergency. The second—and far more alarming—is the new technical definition of the Aravalli Range that threatens to erase the country’s oldest mountain chain from legal protection.

If the government and Prime Minister Narendra Modi do not intervene decisively and halt the implementation of the recent court order, future generations may scarcely believe that a continuous chain of ancient mountains ever existed on Indian soil. The Aravalli hills, stretching nearly 800 kilometres from Gujarat to Delhi through Rajasthan and Haryana, may survive only in textbooks.

This issue will demonstrate whether the state truly works in the interest of the people or capitulates to big industrialists, mining mafias and real estate lobbies. One can only hope that the government does not allow the Aravalli range to disappear merely to serve short-sighted “experts” and profit-seekers eager to mine, build golf courses and construct massive residential complexes.

If the government fails to act, it risks being seen as no different from its political opponents. History shows that power is never permanent. Just as swarms of bees chased away mighty Mughal armies from Aravalli range, a swarm of voters can chase away even governments that have enjoyed repeated electoral victories since 2014.

The irony is stark. At a time when public figures like Sadguru Jaggi Vasudev have mobilised mass movements such as the “Save Soil” campaign, last month’s apex court order introduced a new technical definition of the Aravalli Range. According to this definition, only landforms with an elevation of 100 metres or more above local relief are legally recognised as “Aravalli Hills.”

Environmentalists warn that this narrow definition could strip legal protection from nearly 90 per cent of the range. An internal Forest Survey of India assessment reportedly found that only 1,048 out of 12,081 mapped hills meet this threshold. There is widespread fear that the “de-classification” of lower hills will eventually open vast tracts to mining and commercial exploitation.

The ecological consequences are frightening. The Aravalli range acts as a natural wall preventing the Thar Desert from expanding eastward. Experts warn that even smaller ridges—10 to 30 metres high—are effective in blocking dust storms. Opening these hills to mining is tantamount to inviting the desert to advance into Delhi and eastern Rajasthan.

The rocky structure of the Aravalli’s intercepts rainfall and channels it underground, making the range a vital groundwater recharge zone for north-west India. Destroying these hills is an invitation to drought in a region already battling water scarcity. The range also serves as a barrier against extreme heat waves from the west and supports wildlife corridors used by leopards and other species. Its destruction will further worsen air pollution in Delhi, Rajasthan, Gujarat and Haryana by removing natural dust barriers.

Spread across nearly five million hectares, the Aravalli range is not uniform in elevation or structure. That very diversity is what makes it ecologically resilient. Experts and citizens alike are asking a fundamental question: what moral or constitutional right does any government have to permit the systematic destruction of such a critical natural heritage?

Several rivers and seasonal streams—including the Banas, Luni, Sahibi and Sakhi—originate in the Aravallis. Many have already disappeared due to environmental degradation and over-exploitation. Further loss of the hills will only deepen India’s water crisis.

The disasters awaiting future generations are incomprehensible and when imagination itself becomes terrifying, it is already a warning. History will not forgive any political party, whether the BJP or the opposition, if this injustice is inflicted on posterity and the Thar Desert is allowed to creep to Delhi’s doorstep.

Yet, our parliamentarians did not appear to be concerned about it. Not a word about it from the ‘honourable’ MPs. The opposition and the ruling party accused each other of constant disruptions.

Repeated adjournments following ruckus are no solution. Little effort is made—during or after sessions—to restore discipline and ensure collective responsibility towards the welfare and development of the nation. Jago Sansad Jago. Forget Vote Chori, fight for Aravalli Chori and Save the Nation.

(The author is former Chief Editor of The Hans India)