Wisdom Bytes

Wisdom Bytes

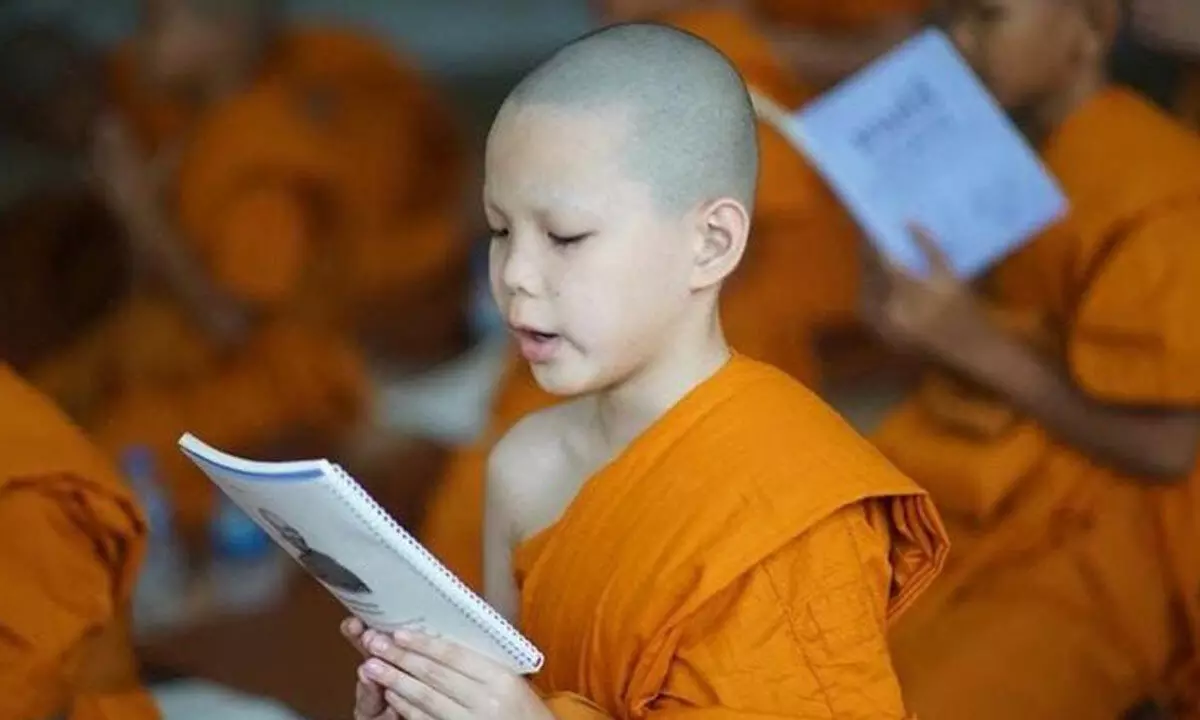

As kids in elementary and high schools several years ago, we were made to learn scores of poems by heart, sometimes knowing their meanings and sometimes not knowing them fully

As kids in elementary and high schools several years ago, we were made to learn scores of poems by heart, sometimes knowing their meanings and sometimes not knowing them fully. They were poems for all contexts, all human interactions. There was poetic beauty, similes, and metaphors from daily life, describing the lofty or petty behaviour of people. This was a genre of literature meant for all ages, called subhashita-s, pithy, attractive sayings encapsulating human nature, human follies, and guiding people. This genre existed in all Indian languages.

This was a nice system of wisdom training through small independent bytes. We now call it emotional training and measure it as the emotional quotient. Even a child of an elementary school would know the interesting examples in these verses. For instance, a poem would say, ‘keep washing the skin of a rat for a year, it continues to be black; it is the same with an obstinate person if we want to teach something to him’. Another poem says, ‘a berry looks grand from outside, but if you open it, you see worms in the belly; so is the case with a coward’. Another would say, ‘of what use is outward courtesy without a pure mind, of what use is food cooked in a dirty pot, and of what use is our worship if the mind is polluted’. Another says, ‘a loafer has a loudmouth; a gentleman is soft spoken; does not the bell metal sound louder than gold?’. All these sayings make sense from childhood to old age.

In fact, as we grow old, they make greater sense. They give directions to us about what to do or what not to do. The meaning of the verses sinks deeper and deeper. Louis MacNeice, an American poet, in his poem ‘The Truisms’, writes that these truisms (sayings) which were given by his father to him were as though in a box, and he had forgotten about them. After a long time, having had good and bad experiences and a series of struggles in life, he comes back and opens the box to see these truisms have grown into a big tree. The meaning is that they became more meaningful now.

Sanskrit abounds in such poems. There are collections of thousands of such witty sayings. We do not know whether any other culture has such tradition. Mahabharata appears to be the fountainhead of this genre. Human relations and statecraft are told by the intelligent minister Vidura to the blind Dhritarashtra. This portion, known as Vidura-Niti, is a masterpiece. Later texts like Panchatantra carried on this practice, giving us a treasure house of verses in Sanskrit. Modern critics may dismiss them as didactic, but it does not matter, the treasure has great value.

Learning such crisp and pithy verses is also a good way of learning and teaching a language. Verses, by their very nature, are easy to remember. Comparisons are drawn brilliantly, with an effective choice of words and hence they get imprinted on the mind. Parents will find them useful in multiple ways – teaching the right pronunciation, teaching life truths, and making the kids emotionally strong.

(Writer is former DGP, Andhra Pradesh)