Decadent despots or barriers to British hegemony? Awadh’s early Nawabs - and Begums - re-examined

The Nawabs of Awadh have long been associated with opulent lifestyles, refined cultural sensibilities, and political passivity.

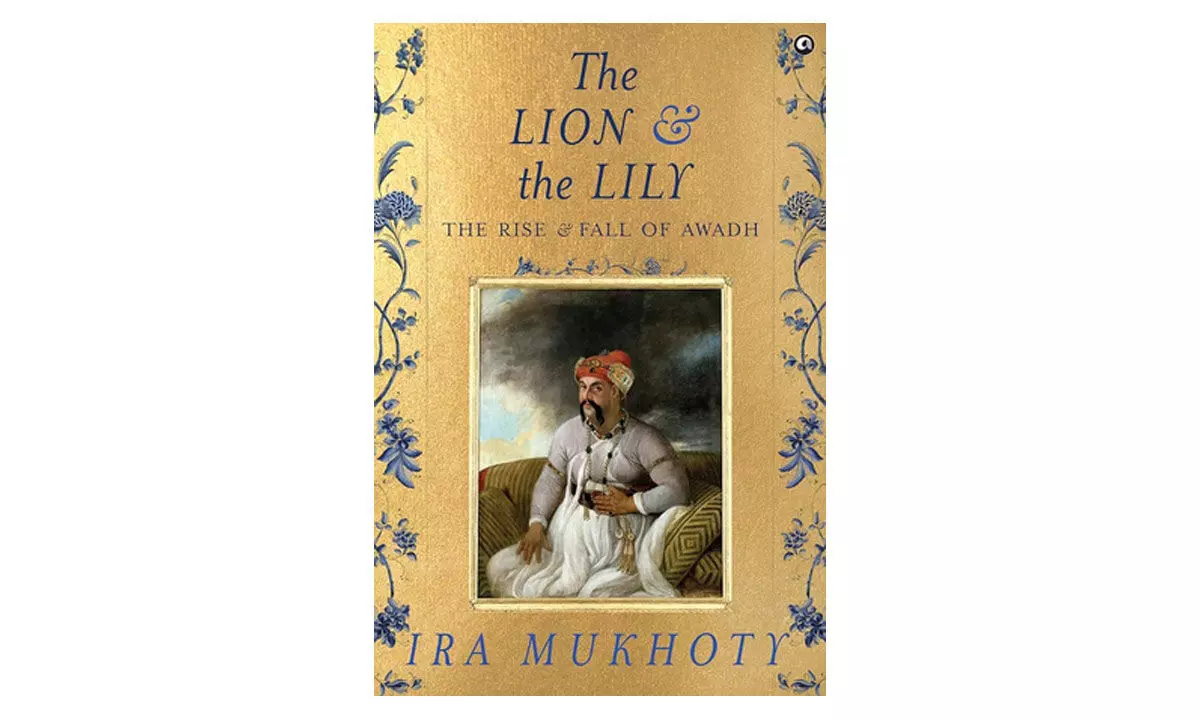

The Nawabs of Awadh have long been associated with opulent lifestyles, refined cultural sensibilities, and political passivity. However, is this reputation truly deserved, or is it the result of a historical smear campaign orchestrated by a foreign power bent on territorial domination? In “The Lion and The Lily: The Rise and Fall of Awadh” (Aleph Book Company), author Ira Mukhoty delves into the complex legacy of Awadh’s early rulers and challenges the prevailing narrative of their decline as being inevitable and self-inflicted. Instead, she posits that the Nawabs, along with powerful Begums, were formidable political players who resisted British expansion far more effectively than they have been credited for.

Mukhoty, known for her works on Indian history, such as Heroines: Powerful Indian Women of Myth and History (2017) and Akbar: The Great Mughal (2020), presents a nuanced portrayal of Awadh’s first few Nawabs against the backdrop of the 18th-century global power struggle. Far from passive spectators, she argues that these rulers adeptly navigated a turbulent political landscape dominated by the British and French rivalry. Her analysis reveals that India was more than just a battlefield for European powers; what transpired on the subcontinent had far-reaching consequences, including on the other side of the world, as in the case of British America.

In this meticulously researched book, Mukhoty takes aim at the “monochrome recording of Indian history” that has long painted the British conquest as inevitable and portrays Indian rulers as either resigned to their fate or woefully inept. This version of history, she argues, is deeply flawed and overlooks the fierce resistance put up by rulers like the Nawabs of Awadh. Citing Maya Jasanoff’s Edge of Empire: Lives, Culture, and Conquest in the East, 1750-1850 (2006), Mukhoty emphasizes that the British faced considerable challenges from indigenous powers and that their rule in India was far from a foregone conclusion.

The book opens with an account of the 1746 French victory over Mughal forces in Madras, led by the son of the Nawab of the Carnatic. This incident, long before the Battle of Plassey, underscores Mukhoty’s thesis that European domination was neither swift nor uncontested. The French, despite their success, did not follow through, allowing the British to eventually gain a foothold. However, Mukhoty’s analysis suggests that had the Nawabs of Awadh, Mysore’s Tipu Sultan, or the Maratha leader Mahadji Scindia formed a stronger alliance, the British path to supremacy might have been blocked.

Mukhoty’s exploration of the Nawabs focuses on the first four rulers, with particular attention given to the latter two, Safdar Jang and Shuja-ud-Daula. Yet, this is not solely a story of male rulers. The author brings into the spotlight two influential women: Nawab Aliya Sadrunissa, wife of Safdar Jang, and Aliya Amat-uz-Zehra, better known as Bahu Begum, the wife of Shuja-ud-Daula. These Begums, far from being confined to the zenana, wielded immense power and played crucial roles in political affairs. Living in Faizabad, they controlled vast fortunes and were deeply involved in events like Raja Chait Singh’s revolt against the British. Their influence was significant enough that the British vilified and persecuted them, with Warren Hastings being impeached for his actions against the Begums of Oudh.

“The Lion and The Lily” also sheds light on a cast of Indian rulers, noblemen, courtiers, and adventurers, all navigating the treacherous waters of 18th-century politics. Figures like the loyal courtiers Tikait Rai and Jhau Lal, power-hungry opportunists, and the indomitable French adventurers (beyond Claude Martin) make for a rich tapestry of characters.

In addition to politics, the book delves into the evolution of Awadh’s culture, with sections dedicated to religion, literature, art, fashion, and cuisine. The development of the famed ‘Ganga-Jamuni’ tehzeeb, a harmonious blend of Hindu and Muslim cultural influences, is also explored. Mukhoty’s portrayal of this era provides a fuller, more complex picture of the Nawabs, presenting them as skilled rulers rather than the effete caricatures often depicted in colonial accounts.

While “The Lion and The Lily” focuses on the early Nawabs, Mukhoty leaves readers hoping for a sequel that continues the story of Awadh’s later rulers. For now, her work stands as a compelling reexamination of an often-maligned dynasty and a valuable contribution to our understanding of India’s pre-colonial history.