Arunachal's Idu Mishmi people regard tigers as their elder brothers

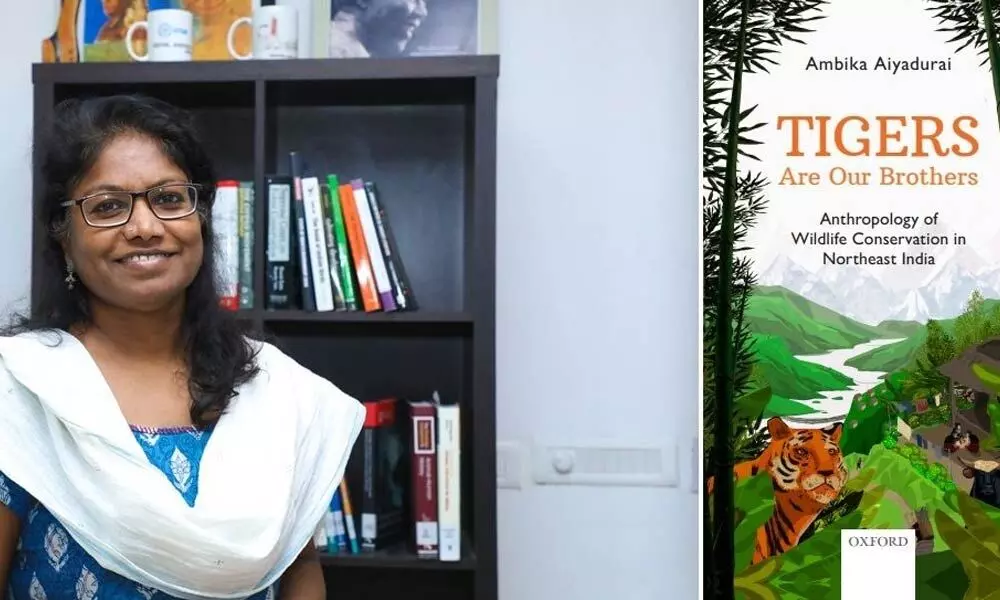

Ambika Aiyadurai

The Idu Mishmi sub-tribe of Arunachal Pradesh's Dibang Valley believes that tigers are their elder brothers

The Idu Mishmi sub-tribe of Arunachal Pradesh's Dibang Valley believes that tigers are their elder brothers. Killing tigers is, for the Idu Mishmi, a taboo. While their beliefs support wildlife conservation, they also offer a critique of the dominant mode of nature protection, Ambika Aiyadurai, Assistant Professor in Humanities and Social Science at IIT-Gandhinagar, writes in "Tigers Are Our Brothers" (OUP).

The book is an outcome of her PhD thesis in Anthropology from the National University of Singapore and is based on long-term ethnographic fieldwork mainly in the Dibang Valley and also in other parts of Arunachal Pradesh. Her research critically engages in debates of wildlife conservation and its impact on the lives of the Idu Mishmi.

The book, a timely reminder on World Wildlife Conservation Day (December 4), argues for an inclusive, culturally informed, and people-centric approach to wildlife conservation. Based on in-depth interviews, archival research and living with an Idu Mishmi family, it presents rare insights into how local communities negotiate their lives, as their landscape is fast-changing, and forcing them to both participate and also question the nature of development and conservation.

"I had initially avoided focusing on tigers as part of my research; I did not want my research to centre on a high profile animal or a site. However, during my exploratory visit to Koronu village (Lower Dibang Valley) adjacent to Mehao Wildlife Sanctuary, in 2012, I heard stories about the rescue of tiger cubs in the Dibang Valley. I was shown a letter from the forest department that pleaded for help from the villagers in providing information about a tiger-killing incident.

"The letter had become a sort of joke and the villagers ridiculed and questioned the naivet� of the forest department expecting the villagers to identify the killer of the tiger. People told me about the visits made by scientists and NGOs to the Dibang Valley. As I began to assess the situation, I felt that the Dibang Valley had all the features that I intended to research: the interest of NGOs and wildlife biologists, scientists, the imposition of state authority, human-wildlife conflict, and the very vocal Idu Mishmi community," Aiyadurai told in an interview.

"The book begins with the rescue of tiger cubs by a conservation NGO in Dibang Valley of Arunachal Pradesh, after which the district witnessed a series of conservation interventions and research projects by state and NGOs "and this remote corner of India transformed itself into a site of high profile visits of wildlife researchers and conservation NGOs", Aiyadurai said.

"They mapped the tiger habitat, assessed the tiger and its prey population and this information led to the proposal of a tiger reserve. While the researchers and NGOs were busy studying the wildlife, the Idu Mishmis were anxious with the several actors visiting the district to study tigers and their habitat. They were particularly curious about the 'new' found interest in tigers," she added.

The residents of the Dibang Valley often stated that they do not harm tigers and in fact their kinship relations with tigers are helping the tiger population. "The fear of getting intertwined with the state's 'ever-reaching hands' and losing their lands for tiger conservation was the chief reason behind their anxieties," Aiyadurai explaned.

"While some welcome the idea of a tiger reserve with the hope of employment, others worried that the ownership of their lands, forests and mountains will be compromised. This is one of many issues that brought researchers, scientists and the state in direct confrontation with the people of the Dibang Valley. A common grievance of the residents was the non-consultative approach of the state and the non-participatory nature of researchers.

"The Idu Mishmi felt a sense of mistrust towards the forest department and the research team members. This has resulted in mild intimidation and resistance, as well as hesitation or even refusal in participating in research activities. Moreover, there was a difference in the perception and understanding of nature as well as its protection and conservation that the book examines," Aiyadurai elaborated.

Why did she decide to write this book?

"Wildlife conservation narratives in India tell us only a partial story. The story of charismatic species, the 'discovery' of a species, news about undocumented landscapes, the use of high tech tools in research - all this makes a happy story, but the 'human' story in wildlife research and conservation is largely invisible, specially, narratives about people living in the conservation sites. "Conservationists do not adequately address the social issues that are important for effective conservation. Ignoring views of those impacted by conservation is often not discussed in the dominant scientific and state narratives of conservation.

"The aim of writing this book is provide a glimpse of how wildlife conservation impacts the lives of local communities and to provide multiple narratives and alternate approaches to wildlife conservation," the author said. Engaging with different interest groups may provide new and better ways of conserving landscapes and wildlife, without antagonising the local inhabitants. "The story of the tiger brothers of the Idu Mishmi is a reminder that we must consider alternate ways of knowing nature and to give space to indigenous voices to make conservation more socially meaningful and inclusive," Aiyadurai emphasised.

Considering the success of tiger conservation in Arunachal Pradesh can this model be replicated in other parts of India?

"Each area is different with unique people-animal relations and cultural ethos. One has to discuss with the local communities and take them into confidence before beginning any survey or wildlife projects. What would work in Arunachal, may not work in other parts of the country. It is very important to have a sensitive approach with knowledge of social sciences and anthropological perspectives of local residents of the area. "Therefore, biologists and researchers need to be sensitized towards local people's needs and more importantly, they should acknowledge people's relations with wildlife, and how they value their immediate surroundings. Partnering with local communities, power sharing in decision making and including their views and opinions through discussions and dialogues may be one way to take this forward," Aiyadurai maintained.

She also pointed out that using their notion of a sibling or kinship relation with tigers, the Idu Mishmi question the state's idea of converting the Dibang Wildlife Sanctuary into Dibang Tiger Reserve, as well as the scientific surveys of tigers and habitat mapping undertaken for this purpose.

"My research also highlights how the Idu Mishmi relate to tigers and how these relations contradict the versions of human-animal relations laid out by the state and science. The state considers tigers as its national property, while biologists' view tigers as an endangered species. Both these understandings stand in opposition to the local interpretations of tigers and, more generally, nature itself," Aiyadurai said.

She also realised how sensitive the issue is on the ground for the Idu Mishmi, which is often not understood by the visiting state authorities and researchers.

"The visiting researchers carried back data on the tigers, their habitats, and their prey, but not adequate information was gathered on the loss that people incurred because of tiger attacks on their domesticated mithuns (mountain cattle). Though their reports carried some information about the Idu Mishmi, overall they appear in the reports in a cosmetic sense that lacks the complex socio-cultural and political understanding of their lives and the issues they face.

"As a researcher, I wanted to approach the central subject of my study from multiple points of view. What does the story of the Idu Mishmi, wildlife biologists, and the forest department tells us about the practice and ideology of biodiversity conservation? I would like to highlight the deficit of the 'social' in nature conservation and the need for an interdisciplinary understanding of the subject," Aiyadurai said.