An exhibition exploring places that once defined New York City

This spring, the New York Historical Society debuts Lost New York, a new exhibition exploring the places that once defined New York City.

This spring, the New York Historical Society debuts Lost New York, a new exhibition exploring the places that once defined New York City. The exhibition invites visitors to experience the city’s lost landmarks, such as the original Penn Station, Croton Reservoir, Chinese Theater, and river bathhouses.

Throughout the exhibition, community voices bring these lost sites to life: a woman recalls attending the Old Met Opera House in 1939, a Broadway carpenter reminisces about a photograph of his father in front of the Hippodrome Theatre, and a choir director reflects upon the demolished Harlem Renaissance monument Lift Every Voice and Sing.

Curated by Wendy Nālani E. Ikemoto, vice president and chief curator of New York Historical, Lost New York showcases treasures from the Museum and Patricia D. Klingenstein Library collections and captures both the dynamism of an ever-changing city and the importance of preserving pieces of our otherwise vanishing past.

The exhibition is on view from April 19 – September 29, 2024. To welcome the new exhibition, pay-as-you-wish Friday evenings will expand from 5–8 pm and include live vintage music and speciality “lost” cocktails during the spring and summer months.

“Lost New York invites visitors to wander through the echoes of a city unfamiliar to what they know now,” said Dr. Louise Mirrer, president and CEO of New York Historical. “We’re excited to welcome visitors throughout the run of the exhibition and especially on Friday nights when the galleries will be filled with vibrant music, nostalgia, and good cheer.”

“Lost New York delves into the many and deep layers of this city. I hope visitors will delight in discovering the landmarks that once defined the places they know but also consider the serious issues, like gentrification and environmental devastation, that drove their loss and reflect upon the importance of preserving our past,” said Dr. Wendy Nālani E. Ikemoto. “It has been an honour to connect with members of our community and learn about their experiences with these lost places. Their voices enliven and personalize the exhibition and sustain the memory and meaning of these sites.”

Exhibition Highlights

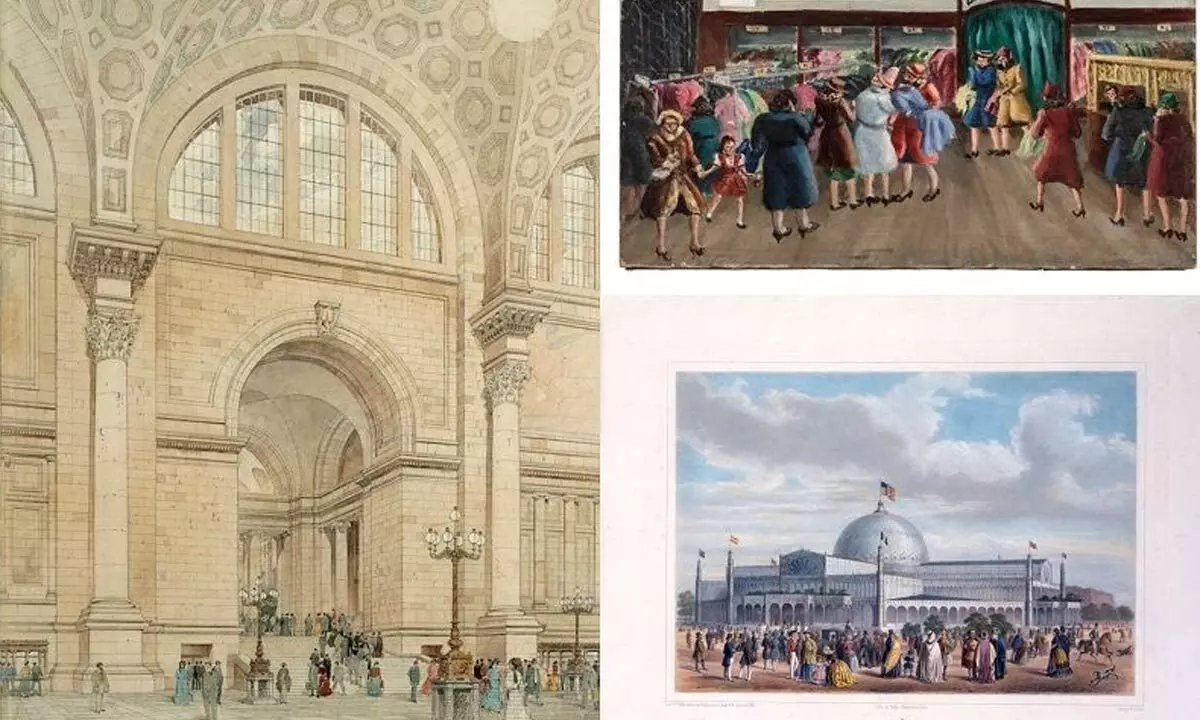

Comprising more than 90 paintings, photographs, objects, and lithographs, the exhibition offers captivating glimpses into the city’s rich architectural heritage and vibrant past. Featured is Jules Crow’s vivid depiction of the Pennsylvania Station Interior in 1906, a masterful watercolour capturing the grandeur of the original Beaux-Arts masterpiece designed by McKim, Mead, and White. Opened in 1910, the building stood for only 54 years. Its demolition spurred the creation of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission two years later.

François Courtin’s lithograph captures another bygone structure displaying the grandeur of New York’s Crystal Palace during the 1853 Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations. Rising majestically in what is now Bryant Park, this architectural marvel once hosted technological wonders from across the globe, offering a glimpse into an era of innovation and boundless imagination. Steps away was the original Croton Reservoir, built to increase the city’s water supply, as depicted in an 1850 lithograph by Charles Autenrieth. Its massive Egyptian-style walls became a popular promenade spot for New Yorkers. Parts of the original stone structure can still be seen on the lower level of the New York Public Library on 42nd Street, which rose in its place.

While sign painter De La Prelette Wriley shows off his own business in the 1837 oil on wood panel, No. 7 1/2 Bowery, the painting features another antiquated hallmark of early New York—a pig roaming the streets. A low-maintenance and high-protein food staple, pigs wandered freely through the city until 1859, serving as New York’s first garbage management system by eating scraps off the streets. Showcasing another common animal of the city’s early streets, William Seaman’s 1850 oil painting Knickerbocker Stage Line Omnibus depicts New York’s first form of mass transit: large horse-drawn stagecoaches that carried about a dozen people at a time and ran along designated routes.

Complementing many of the works on display are observations from various New Yorkers sharing their memories of the places depicted. These community voices include an artist who, as an LGBTQ+ youth and aspiring artist, purchased a t-shirt from Keith Haring’s Pop Shop; a woman from a self-described multigenerational family Yankee “fandom” who remembers watching David Wells and David Cone pitch perfect games at the old Yankee Stadium; and a cultural worker who imagines the cross-cultural conversation that led Samuel Northcote to mistitle New York City’s first Chinese-language theater in his 1899 painting of it.